ROSE JACOBS | JAN 16, 2018

SECTIONS BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE ECONOMICS

Superstition can affect people’s decision-making in a variety of ways, research shows. Association with a lucky number can alter the price of an apartment, for instance, or drive short-term inflation in a stock’s price. But superstition’s sway over our lives doesn’t stop with discreet choices. Research indicates that it can play a significant role in determining long-term success.

Louisiana State University’s Naci H. Mocan and Han Yu investigated the connection between a person’s educational achievement and the year of the Chinese zodiac in which he or she was born. Using data from China, where a traditional superstition holds that children born in the Year of the Dragon are destined for good fortune, they find that “Dragon children” did indeed outperform their non-Dragon peers. This was the case even when intelligence, personal ambition and self-confidence, and family educational and economic background were factored out.

RECOMMENDED READING

How to profit from magical thinking

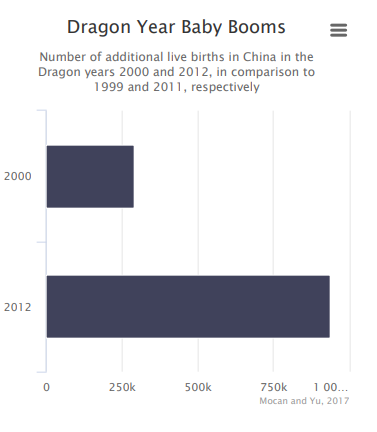

The researchers had expected to find the opposite. The number of marriages in China rises in the two years before a Year of the Dragon (which occurs every 12 years, most recently overlapping with 2012 and 2013), as future parents target Dragon birthdates for their offspring. As a result, the birth rate in China rises signicantly in Dragon years, according to Mocan and Yu. Logic might suggest this would make life difficult for Dragon children: larger class cohorts can mean more competition and less teacher time. But analysis of two separate data sets indicates Dragon children outperformed their peers on a nationally administered university entrance exam and were more likely to have attained at least a college education. A different set of data suggests Dragon children enjoyed higher middle-school test scores.

The data also offer a possible mechanism for the phenomenon: the behavior of parents. Parents of children born in Dragon years are more likely to take some key actions that go on to improve the children’s lots in life, from checking in with teachers during the school year to giving out higher allowances to expecting their children to perform fewer household chores.

Although parents may expect the best from their Dragon children, when kids themselves were asked to estimate their own talents and share their expectations for their own future, Dragons weren’t more likely to rate their intelligence highly nor to shoot higher in terms of educational or career goals.

“We find that parents of Dragon children have higher expectations for their children in comparison to other parents, and that they invest more heavily in their children in terms of time and money,” Mocan and Yu write. “Even though neither the Dragon children nor their families are inherently different from other children and families, the belief in the prophecy of success and the ensuing investment become self-fulfilling.”

1/22/2018 Why China’s ‘Dragon children’ are such a success at school | Chicago Booth Review